In part 1 of this article, I wrote about two of the fundamental challenges with the ‘Play-to-Earn’ gaming model. The first one related to the Diablo Auction House Dilemma, stating that pay-to-win shortcut to endgame content is not a sustainable solution to generate revenue in a ‘Play-to-Earn’ economy. The second problem related to the importance of fun-focused game development, as fun gaming is the main source of attraction for value injectors into the ecosystem.

Today I’ll be diving deeper into another problematic area that makes the creation of sustainable Play-to-Earn economies so complicated.

The Rise of Guilds and Scholars

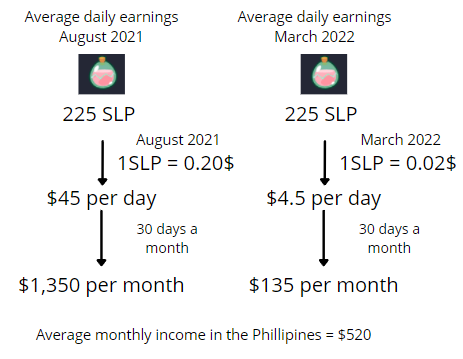

When Axie Infinity started turning heads last year, it kick-started an interesting new development around its economy. In my article, “The Rise and Fall of Axie Infinity”, I explained how whole communities in the Philippines became ‘professional’ Axie Infinity players, trading their day jobs for a new kind of job, playing a game. As more and more people in developing countries woke up to the idea that they could play this game for a living, demand for Axie NFT’s skyrocketed. Back then, the amount of Axie NFT’s (required to play the game) were limited, whereas demand for them was growing explosively.

The result of this gap between supply and demand was that the average price of an Axie NFT also increased rapidly. So much so that the people in developing countries were no longer able to afford the high cost of entry. Luckily for them, investors from developing countries were ready to swoop in to save the day. You see, over in the westernised part of the world, crypto-game enthusiast were also taking part in this developing new economy. Yet due to the much higher cost of living in their part of the world, they found the average daily earnings for personally playing an Axie Infinity team far from lucrative.

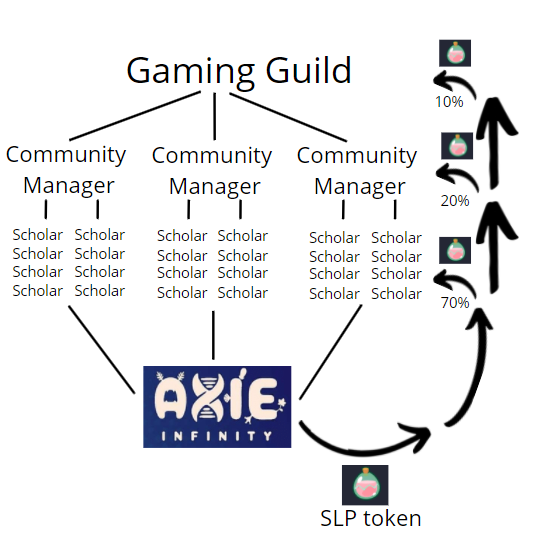

However, using the science of scalability, it was discovered that Axie NFT’s could be ‘lent out’ to players in developing countries, who would play the game and split the winnings with the NFT owner. This way, players with more starting capital could scale up their earnings to become more lucrative for their higher cost of living areas, and players from developing countries could skip the high cost of entry and get started on the ground floor by borrowing an NFT to play.

This system was quickly formalised under the term ‘scholarships’, and these scaling establishments referred to themselves as ‘gaming guilds.’ These guilds would buy up all the NFT’s on the market and create massive breeding operations to create more, whilst simultaneously recruiting and managing an ever-growing team of ‘scholars’ to do the legwork. Guilds were quickly hailed as a revolutionary solution to the escalating NFT price wars, their websites filled with ‘success stories’ from all of their scholars who were playing games to pay for their expenses and families.

The Moral Dilemma

But are these guilds really the innovative solution that many seem to claim they are? Or are they a group of exploitative opportunists, who are just as much part of the problem as they are the manufactured solution?

I’m not the one to answer that question, but it can be argued that without the increasing demand pressure from speculators and gaming guilds, the cost of entry to buy these NFT’s would be lower.

Then again, on the other side of the spectrum, there are many examples of life-changing money being earnt by people who were recruited and trained by gaming guilds, and subsequently went on to earn much more money playing games than they could with other jobs available to them.

The Value problem

In my previous article we talked about value extractors and value injectors, and how both need to be balanced in order to create a sustainable P2E economy. It can easily be argued that ‘scholars’ fall under the category of value extractors, as they are motivated by their guilds to create as much ‘revenue’ as possible. They treat ‘Play-to-Earn’ games not as games that primarily provide them with relaxation and enjoyment, but as jobs, that provide them with income and a certain dependency on it.

This means that scholars are categorically defined as the most extreme value extractors, entirely motivated by their mission to extract the maximum amount of value from a P2E economy. And although it’s heart-warming to read stories of struggling communities suddenly flourishing by playing online games, it must be understood that P2E games cannot survive when the majority of their playerbase consists of scholars. When scaling guild organisations focus too much on growing their scholarship community, they are only adding to the destruction of the economies that they are trying to exploit.

The solution to this, which I will further explore in a future article, lies within gaming guilds using their revenues in order to help transition the casual gamers into the P2E revolution. If a gaming guild community can offset their value extractors by also bringing in more value injectors, they can help balance the scales and truly become part of the solution.

Conclusion

It can be argued that Gaming Guilds are more than just a scholarship facilitation program, as they have evolved to become communities of social connection centred around their shared interest of gaming. However, P2E game builders are waking up to this economical imbalance, and many are currently already working on smart-contract based services that facilitate the scholarship model directly within their in-game marketplaces, making the financial involvement of Guilds obsolete.

Once Gaming Guilds are cut off from this supply of passive income, it will be interesting to see how they will evolve their community interaction, and whether they will still be incentivised to stimulate their members when they are no longer financially being rewarded to do so.